The January 2005 commuter rail disaster in Southern California (train hit an SUV, 25 dead) points up a serious passenger rail safety problem; one we think can be greatly reduced without much trouble or cost:

To save time and space, many commuter trains operating back and forth along linear routes run forward one direction, backward the other. The way it works is that the last car is equipped with a cubicle and controls so that during each return trip the engineer controls the engine from this cubicle, driving the train “backwards”. This is a good practice, as it saves the hassle of moving the engine from one end of the train to the other twice every round trip and eliminates the need for huge turn-around track loops. But it makes the train more vulnerable to derailment in the “push” mode. When the train is running in the “pull” mode (engine first), the weight and shape of the engine tend to push obstructions out of the way.

Most death, injury and property damage resulting from auto-train collisions (at least to the train) can be avoided if the train does not leave the tracks. This can be accomplished by shielding the train and its wheels from the debris that gets under same and causes derailments. Hence the “CarCatcher”.

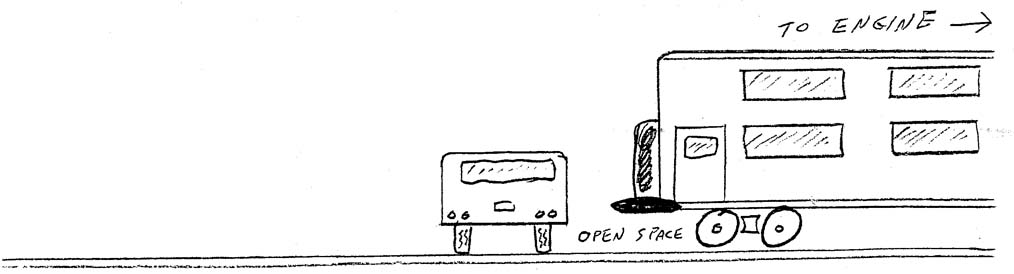

The vulnerability of an unprotected leading passenger rail car is illustrated thus:

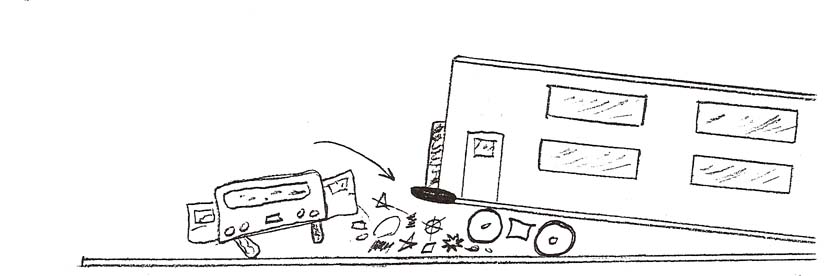

When a train running in “push mode” hits an automobile, the latter or its debris tends to roll under the exposed train wheels, lifting them from the track:

(Once a set of train wheels leaves the track, it rarely returns to same).

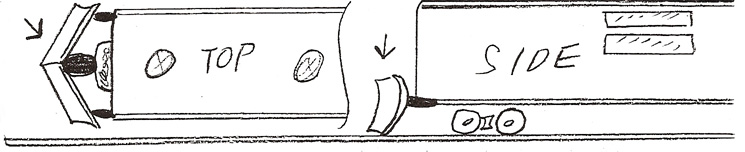

To minimize the event of derailment in train-car or other track-obstruction accidents, we propose the CarCatcher, a device that might look a little like this, or a lot prettier:

The CarCatcher would attach to the rear of each train, using the regular coupling supplemented by a horizontal brace or shock absorber assembly. We picture a kind of cross between an old-fashioned cow catcher and a snow plow. The device could be painted to suit its train, and could be designed in several styles to match or complement the design of the train—-modern, retro, etc. As illustrated below, the device would push the obstruction and its larger pieces of debris off the tracks, helping to keep the train on the rails.

The potential market for the CarCatcher consists of every train in the world that operates in the push-pull mode.

Cost would of course be variable, since we envision several sizes. The design and shape of the CarCatcher will have to allow for train size and weight, the engineer’s clear view of the tracks ahead, and perhaps to which side one might wish to shove the obstruction. We think the most expensive model we can imagine might cost less than some pickup trucks. Being a New Mexico group, of course we would like to see the CarCatcher designed and built in New Mexico for sale here and everywhere else.

In summary, this thing is not likely to do much good if a semi or another train gets stuck on the tracks, but many rail-auto accidents are caused by an inattentive or suicidal driver driving something small enough to be diverted by one size or another of CarCatcher. This device might even improve the outcome for the affected auto and occupants. We think that the potential savings in lives, limbs and property promised by the CarCatcher more than justifies its cost and possibly strange appearance.

RAILS Inc.

PO Box 4268

Albuquerque, NM 87196

www.nmrails.org

rails@nmrails.org